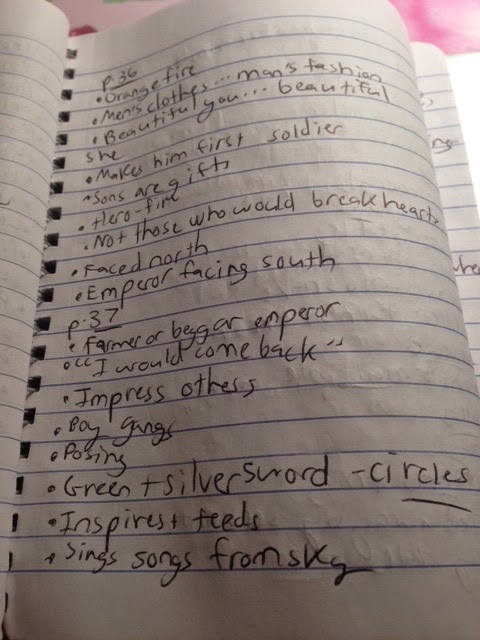

"I inspired my army, and I fed them. At night I sang to them glorious songs that came out of the sky and into my head. When I opened my mouth, the songs poured out and were loud enough for the whole encampment to hear: my army stretched out for a mile." (Kingston 37)

Kingston, Maxine Hong. "White Tigers." "The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts." New York: Knopf, 1976. 37. Print. At this point, the narrator, having completed her warrior training, has returned home, assembled an army, and is now camped out with them. I'm interested in this passage because it describes clearly the relationship between the narrator and her all-male army, an interaction that is missing in the original Ballad of Fa Mu Lan. I'm curious to investigate why Maxine Hong Kingston chooses to go into detail about this relationship.

What stands out to me about the content is, firstly, how the narrator seems to have a power over her army that goes beyond just being their leader. She gives them emotional support as well as physical. She's not only their leader, she's also their friend. Also, it stands out to me that her main way to inspire them is by singing. This seems significant. In addition, it's surprising that the songs just come from the sky. She doesn't need to put any effort into composing and/or performing these songs - it just happens. Almost as if she has no control over it. And she's able to project so well! Also - her army stretches out for a whole mile, according to her! Quite the army to be in charge of.

Style-wise, there's a lot of "I's" floating about: "I inspired my army," "I fed them," "I sang to them," "I opened my mouth," and so on. And while there's a lot of "I's" to describe the narrator, in a few instances the army is described as "them." So while the narrator is being portrayed as an individual who stands out from the rest, the rest of the army - the men - are all grouped together and generalized. They move as a unit, given no individual characteristics. This makes us focus the majority of our attention on the amazing things the narrator is doing, while ignoring the army. In the second sentence of this paragraph, there is no comma after "At night" as one would expect - instead that whole sentence is one blob, void of punctuation. As a reader, it has the same dreamy, hazy effect that the beginning of the story does when the narrator is being lulled to sleep by the stories of her mother. Due to our status quo way of thinking, there is something distinctly feminine about this. The sentence seems to literally embody the action of the songs flowing from the sky into her. Also, she says "I fed them" right before describing the singing, as though the songs are the nourishment she's providing. And the semicolon before "My army stretched out for a mile" made it feel to me like she was bragging.

All of this adds a sense of supreme power to the character of the narrator. While the army is generalized, she is made more and more the individual. She has control over her army, and even over us. But there's something, like I said before, feminine to the way she controls them that I think is central to why Maxine Hong Kingston added it in. This idea of singing for an audience to soothe and comfort them is something we associate with more femininity than masculinity. While she is the powerful bloodthirsty general of a powerful bloodthirsty army, there is also something motherly about her. We never hear about Mu Lan singing to her army, in fact we never hear about her interacting with her army at all. The way she is portrayed - as a completely masculine woman - it seems unlikely she would sing to her army, lest it ruin the facade of strength and power. For the narrator in "White Tigers," though, it only gives her more power. Ultimately, I think this is another way Maxine Hong Kingston is trying to create a woman who is a powerful, skilled warrior, but not one devoid of feminine qualities. She can be a warrior while having her period, while being a wife and a mother, while singing lullabies to her army. And it doesn't impede upon her power and the respect others have for her - it only amplifies it.

Monday, March 30, 2015

Monday, March 23, 2015

Wednesday, March 11, 2015

The Healer Essay Draft

Going

into The Healer by Aimee Bender I had

the same basic assumptions in the back of my mind that I’d have for any text,

one of them being that as I read I would likely come across troubling details

that would puzzle me, maybe surprise or disturb me, and demand analysis.

Indeed, in almost every story I’ve ever read there’s been unsettling parts that

caused me to pull back and think “wait…” When details like these stick out it’s

for a good reason, often because the author is intending them to. They deepen

our understanding of the text and sometimes guide us towards the author’s

message.

And yet while I was reading The Healer by Aimee Bender, the

unsettling and troubling details of that sort didn’t hold up red flags till at

least the second or third time I read it through. Odd details surrounding the

character of Lisa went right over my head while reading. That’s not to say that

I read The Healer the first time

through getting nothing out of it. No, I picked up on other things, other

details that were undoubtedly disturbing. But the ones directly connected to

Lisa went under my radar. And they were big ones too, so big that when I

finally noticed them I was shocked that I’d missed them. So if disturbing and

troubling textual details stand out to a reader, but I skimmed over many

troubling details revolving around the central character of Lisa, then why did

I not pick up on these details while I was reading?

While

it’s not uncommon to miss certain parts of a story the first time through, it’s

unlikely this was the reason I skimmed over the ones I did. Considering that

Bender makes sure our narrator Lisa is only supplying us with only limited

information about herself, it would seem to indicate that we would pay closer

attention to the details she does give us. Another way to consider this

is that it was Lisa’s unusual narrating style that caused details about her to

go over my head. Over the course of the story, Aimee Bender repeatedly flirts

with the fairytale genre. As a reader who hadn’t read much slip-stream before,

trying to read The Healer as a

fairytale made the whole thing easier for me to process. But Lisa disrupted my

task – she simply is not a fairytale narrator, who would typically be a sort of

invisible third party that gives the facts and nothing but the facts, serving

the chief purpose of ushering us towards the moral. No, she is too complex a

human to be invisible, and her narrating style is not factual but a choppy

narration full of questionable information. In Lisa, Bender cleverly blends the

fairytale protagonist with the narrator. I had to make her one or the other, so

I broke her down by emitting details, and in the process managed to

2-dimensionalize her in true fairytale form.

So what exactly

makes Lisa so problematic that I was not able to process her in full? To start,

she is not a neutral, uninvolved narrator who is simply observes and retells

the events of the story. While the majority of the story is devoted to the

bizarre tale of fire girl and ice girl, Bender insists on having Lisa switch

the focus to herself from time to time. An example of this is when Lisa is

telling us about the unusual relationship between Roy and the fire girl when

suddenly she says “It always smelled like barbecue where they were. This made

me hungry, which made me uncomfortable” (Bender 29).

By doing this, Lisa

tries to turn the spotlight on her. It’s distracting and even a little bit irritating,

which is likely why I ignored how troubling what she’s actually saying is.

Moments like this in The Healer have

the same effect as when you’re watching TV and someone behind you is talking to

you. You might turn slightly so you can glimpse them out of the corner of your

eye, but ultimately your eyes are still glued to the screen.

When she does

this, Lisa manages to take just the slightest bit of our focus away from the

story. This is what a narrator never does. Quite the opposite, particularly in

fairytales the narrators want to make the story as easily readable and

understandable as can be. They want to make sure nothing can come between you

and the message of the story.

But that’s part

of the problem with Lisa – she doesn’t seem the least bit interested in

conveying a meaning or moral to us. When she throws in lines that give

information completely irrelevant to the plot like “My own hands were shaking.

I had to force myself to leave instead of going back and watching more” it

seems she’s telling this for herself more than anyone else (Bender 29).

Another issue

with Lisa’s narration is that she doesn’t eagerly watch and record the events

of the story from the sidelines – she deliberately tries to involve herself in

them. Her trip to visit the ice girl in the hospital drastically affects the

rest of the story (Bender 30). If Lisa hadn’t fetched the knife from her

kitchen fire girl would still have her hand and all the subsequent mayhem

wouldn’t have ensued (Bender 32). She has the ability to alter the events in

such a powerful way that this alone would make her seem to be the protagonist

of the story.

Not only that,

but she desperately craves recognition and respect from fire girl and ice girl.

In an almost childish manner Lisa wants the two girls to remember her name, for

example when the ice girl doesn’t remember who she is, it says “I was annoyed.

I’m in your science class, I said, Lisa” (Bender 30). Not only does she appear

to be telling the story to prove something to us – she also seems to want to

prove something to them. In a way, she seems like a narrator who wants to be

more than a narrator.

An even bigger

flaw (though I suspect it was intentional) in Bender’s choice of Lisa is a

narrator is that she’s too human.

That might sound strange. But think about it, in Cinderella who are we supposed to relate to? The monotonous

narrator who starts us out with “Once upon a time” and gently nudges us the

rest of the way? No, we’re supposed to relate to Cinderella, and to a certain

extent the other characters as well.

Yet then again,

in characters like Cinderella there isn’t much to relate to. They’re these

2-dimensional characters that lack substance. But if Cinderella is

2-dimensional, the narrator of the tale is only 1. If Cinderella is barely

there, the narrator is invisible.

Going back to

Lisa being too human, there are a few specific points in the text that make

this true. Firstly, when she is describing J. and inventing scenarios where

he’d make a speech about her, she tells us “Today we focus on Lisa, J.’s voice

would sail out, Lisa with the two flesh hands. This is generally where I’d stop

– I wasn’t sure what to add” (Bender 28). This demonstrates that she is only

able to describe herself in comparison to others. We get no other physical

characteristics about her. To Lisa, having only flesh hands while ice girl and

fire girl have special hands is a part of her identity.

But isn’t this

something we all can relate to? We compare ourselves to other people

constantly, considering that things they have and we don’t are a flaw on our

part. This is how Lisa feels about the two mutant girls’ hands. While others

might be scared of the mutants, particularly, fire girl, Lisa is fascinated by

them. When fire girl cuts off her arm and then her entire arm blazes up, Lisa

says “I still thought it was beautiful, but I was just an observer” (Bender

33). She sees herself as normal and plain in comparison to them. They are the

special, important people who sit in the very front and the very back of the

class while Lisa blends in in the middle (Bender 30).

This is not the

only thing about Lisa that we can in fact relate to. Another is how she fears

being responsible for bad occurrences and immediately puts her guard up when

discussing them. One instance of this is when Lisa is about to tell us about

Roy and the fire girl, but first she says “I found them first and it was

accidental, and I told no one, so it wasn’t my fault” (Bender 28). Although at

this point we have no idea what she’s talking about, she sets us up with a

disclaimer first.

I for one can

relate to this. I’ve certainly had times where I’ve been about to describe

something that happened to someone and I say that it wasn’t my fault before

I’ve actually told them anything. It’s this defense mechanism. We have this

fear that if we give someone the chance to judge us they will, and they won’t

like what they see. Lisa seems to care about this too. She’s tremendously

insecure – she holds other people’s opinions above her own. It’s not a healthy

habit. It’s probably one of the worst things we do to ourselves. But reading

that Lisa does it too humanizes her for us.

Interesting

that these parts of Lisa that we can relate to are all negative things. And the

parts we can’t relate to are even more negative. Beyond her defense mechanisms

and her insecurity, she’s also extremely troubled. As an individual, I mean –

she’s the sort of person you’d expect to see on the news or find in an insane

asylum. The details about her that I didn’t notice while I was reading were

mainly the ones that made her seem the most crazy.

An example of

this is how when she’s describing Roy to us, she’s giving us very cryptic and

unsettling details about herself and her relationship to him, some of which

being “Some Saturday when everyone was at a picnic, I wandered into the boys’

bathroom” and “He’d spelled OUCH on his leg” (Bender 29). The first one is

completely bizarre – she just wanders

into the boys’ bathroom. Not something that happens every day. It’s unlikely

she really just wandered into the bathroom. There’s something else going on

that she’s not telling us. That idea only intensifies in the second quote I

listed. She knows what he cut into his leg, which means that he would’ve had to

role up his pants for her to see. So there’s more to there relationship than

she’s letting on.

Continuing on

the troubling aspect of Lisa thread, later in the story she brings up J. again

but in much stranger context: “Now we stood together in the middle of a busy

street, dodging whizzing cars, and I’d pull him tight to me and begin to learn

his skin” (Bender 34). Not only does this imply that Lisa hallucinates or at

least is very… imaginative – it also

has the strange part about “learning his skin,” whatever that means. These

parts alienate her to us – she is no longer the narrator we can relate to, not

that she really should be in the first place. Suddenly she’s this troubled

individual who is demanding attention more energetically than the actual plot.

Again, she’s taking us out of the story, disobeying her call of duty as

narrator and veering more into the protagonist realm.

In addition to

drawing attention away from the story itself, these troubling parts make us

wary to trust her as a narrator. If she hallucinates, if she’s this screwed up,

how can we completely believe anything she says? How can we be sure it’s not

just all a trick of her imagination? And this is only one of the reasons she’s

an unreliable narrator – she also only “thinks” and is “pretty sure” that the

information she’s telling us is truthful. Narrators should be sure of the

information they’re conveying. Why take away anything from Cinderella if you’re still unsure whether she actually went to the

ball?

It would seem

at first that all of these things about Lisa would only make her one of the

reasons The Healer could never pass

as a fairytale. One of the principal other things that seems to interfere with

the fairytale genre is how characters come into the story only to randomly and

abruptly leave – Roy, J., and even ice girl are all like this. But when you

think about it, don’t characters come and go in fairytales too? Sticking with

the Cinderella analogy, when the

fairy godmother leaves, we never see her again. And that doesn’t bother us

while we’re reading the tale, we don’t stop and wonder why she left. That’s

because we don’t have to wonder – we

know, even if we’re not 100% conscious of knowing, that the fairy godmother

served her purpose and now she’s gone.

So characters

disappearing is not in itself a problem. The true problem is that J., Roy, and

ice girl serve no set purpose. You could say that Roy’s purpose is to get fire

girl in prison. However, in fairytales these coming-and-going characters

directly guide the story towards the moral. And The Healer doesn’t have a moral, or at least not the obvious

fairytale-type one that you can’t miss. That all ties back to Lisa. So

ultimately, anything else that makes The

Healer not seem like a fairytale is merely a result of the story’s

unrealistically complex narrator.

Furthermore,

while reading The Healer by Aimee

Bender, I couldn’t help but miss some troubling and unsettling details about

Lisa because she is too complicated and multilayered to process all at once. She

is the one and only reason why The Healer

is not a fairytale, not that characters come and go, not even that the plot

itself is disturbing – after all, the original fairytales were pretty

disturbing and yet they’re still considered fairytales. In Lisa, Bender creates

a dissatisfied, troubled narrator desperately seeking to be someone’s protagonist.

Maybe she hopes to be ours. Whatever the case, in creating this extremely 3D

character Bender is doing more than banishing fairytale archetypes – she’s

taking us on a journey with a character who is an over-exaggerated version of ourselves.

Yes, there’s a lot about Lisa that we can’t relate to, but there is also a lot

we can. She’s human and she’s unapologetically complicated. At first I detested

her. Even now I can’t say I want to be like her, but still, there’s something

refreshing about reading a character who you know (or hope!) that you’ll never

be as messed up as. Fairytale characters are these unrealistic creations – the

good you can never be as good as, the bad you can never be as bad as. Lisa may

have more bad than good in her, but she’s not the villain of The Healer. She’s her own character in

her own category. I think there’s something rather nice about that.

Tuesday, March 10, 2015

Fattened-Up Claim

While it’s not

uncommon to miss details of a story the first time through, it’s unlikely this

was the reason I skimmed over the ones I did. Considering that Bender makes

sure Lisa is only supplying us with limited information about herself, it would

seem to indicate that we would pay closer attention to the details she does give us. So instead, I believe it

is Lisa’s unusual narrating style that caused points about her to go over my

head. Bender repeatedly flirts with

the fairytale genre over the course of the story. As a reader who hadn’t read

much slip-stream before, trying to read it as a fairytale made it easier for me

to process. But Lisa disrupted my task – she simply is not a fairytale

narrator, who would typically be a sort of invisible third party that gives the

facts and nothing but the facts, guiding us towards the moral. No, she is too

complex a human to be invisible, and her narrating style is not factual but a

choppy narration full of questionable information. In Lisa, Bender cleverly

blends the fairytale protagonist with the narrator. I had to make her one or

the other, so I broke her down by emitting details, and in the process managed

to 2-dimensionalize her.

Monday, March 9, 2015

Text Explorations

Leads from Formula to Explore:

·

“Troubling

details” – what about these details makes them troubling? What do they have in

common with each other? What about them makes it strange that I missed them?

·

“Flirts

with the fairytale genre” – in what ways does Aimee Bender do this? What

elements about The Healer make it not a fairytale?

·

“Too

complicated and problematic” – what about Lisa makes her so problematic, more

so than the fire girl and the ice girl?

·

“Details

of her personal life” – what details do we get? What details don’t we get? Any guesses why?

Passage 1 – page 28

At this point in the text Lisa is taking

a break from the action of the story to tell us about J. and her thoughts on

him.

I chose this passage because it’s one of

the times in the text where Lisa turns the focus on her instead of on the

events of the story. By exploring this passage I hope to capture what about

Lisa makes her so complicated and 3D that I had to simplify her while I was

reading.

Passage:

“Today we focus on Lisa, J.’s voice would

sail[1]

out, Lisa[2]

with the two flesh hands[3].

This is generally where I’d stop[4]

– I wasn’t sure what to add[5].”

1: Word

Definition/Wording/Figurative Language/Connection: The OED defines “sail” in a

few particularly interesting ways, the most interesting being simply “To

dance.” This idea of J.’s voice dancing out has this sort of calm musicality to

it. For Lisa, these strange daydreams seem to calm and relax her. They seem to

engulf her and lull her to sleep like the red poppy field in The Wizard of Oz. She loses touch

completely with reality, another example of this being when she says “I was

busy for a second renaming myself Atlanta when I looked over and saw how

nervous and scared she was” (Bender 32). She spaces out often, but this in a

way humanizes her – it’s something we can relate to. Which is part of the

problem. We’re not supposed to relate to the narrator – we’re instead supposed

to feel a connection with the characters of the story. She’s not a reliable

narrator – she recounts information only being “pretty sure” it’s what actually

happened. Her train of thought jumps around like that of Victor in Sherman

Alexie’s short story. She is too much of a blend between a protagonist and a 3rd-party

narrator. I had to categorize her as one or the other.

2:

Wording/Syntax/Connection: The repetition of Lisa’s name in this sentence seems

pointed. It’s like she wants to make sure we know that it’s about her. There’s

something strangely self-centered about her in some parts of the story, like

her desperate need for the fire girl and the ice girl to know her name (Bender

30). She craves being a part of the two girls’ stories instead of just a

bystander. Ah, I’ve come across something! Instead of being a neutral spectator

as a narrator is supposed to be, Lisa

involves herself in the events that take place. She wants to be more than a narrator.

3:

Wording: Lisa feels it necessary to describe herself in relation to others.

Fire girl and ice girl have their elemental hands while she only has flesh hands. Interesting, because

usually when people compare themselves to others, they look for special things

they have that the other person doesn’t. With Lisa it’s the other way around.

By holding her flesh hands next to the ice and fire hands, we can’t help but

see her as not special, as boring, as

normal. That seems to be how she sees herself too.

4:

Wording: It says this is “generally” where she stops, implying that she has

done this multiple times. It seems to be a common pastime for her. But wouldn’t

it get boring after a while, when all she really does is compare herself to the

fire girl and the ice girl? If the part about “flesh hands” is fairly regular,

wouldn’t it get tiresome?

5:

Wording: It says that Lisa “wasn’t sure what to add.” She can say nothing about

herself, be it good or bad, unless it is relation to someone else. She actually

identifies herself by a comparison to fire girl and ice girl. Lisa doesn’t tell

us the story of the fire girl and the ice girl for our benefit because it’s a

nice story with a good moral. She tells it for her own benefit because she believes it defines her as a person. She

cannot live without them. It’s the highest level of dependency and there’s

something almost pitiful about it. Is it possible that, being as wrapped up in

herself as she is and yet so insecure, she tells this on purpose to gain our

pity?

3: Syntax/Connection: The repetition of “and” here not only makes the sentence a run-on, but gives it this sort of uneducated feel. Lisa seems to have a very limited vocabulary – as we said in class discussions, she speaks in choppy sentences. Not something you’d expect from a narrator. It’s one of the many things that makes us wary to trust her story, in addition to her telling us that she only thinks some things happened (Bender 27) and her frequent hallucinations. Narrators, especially of fairytales and fables, are supposed to be trustworthy, because their whole purpose is to convey the message. But as I said before, Lisa doesn’t seem interested in passing along any moral to us at all. Therefore, she feels no obligation to tell the story in a straightforward manner.

Passage

2 – page 28

At

this point in the text Lisa is gearing up to tell us about the fire girl’s

relationship with Roy.

I

chose this passage because it exhibits Lisa’s strange narrating style that

makes her an unreliable narrator and not the kind ideal for a fairytale. By

exploring this passage I hope to deepen my understanding of Lisa’s unusual

narration – I think right now I only have a superficial idea of it.

Passage:

“I

found[1]

them first[2],

and it was accidental, and[3]

I told no one, so it[4]

wasn’t my fault[5].”

1: Word

Definition/Connection: The OED defines “find” as “To

come upon by chance or in the course of events” and “To discover the

whereabouts of (something hidden or not previously observed).” Both these

definitions display the idea of Lisa discovering something new – in this case

Roy and the fire girl. Lisa claims that finding them together was “accidental,”

much like how she tells us she “wandered into the boys’ bathroom” (Bender 29).

She rarely takes responsibility for her actions, insisting that many of these

experiences were merely coincidental. It seems unlikely that she just happened

to come across Roy and the fire girl together, considering she obsessively

stalks the fire girl throughout the course of the book. So she deliberately

tries to mislead us.

2:

Wording: By saying that she came across fire girl and Roy first, Lisa is

not-so-subtly implying that others will come across them later on. She’s

foreshadowing… not even that… alluding

to a later part of the story, something you rarely see happen in fairytales. If

we notice it, it draws us in. Lisa is dangling the information in front of us.

Also, when Lisa insists that she found them first,

it’s almost like she’s staking a claim. She seems to think we’ll applaud her

for it or give her some sort of reward. In this aspect there’s definitely a

childish nature to her.

3: Syntax/Connection: The repetition of “and” here not only makes the sentence a run-on, but gives it this sort of uneducated feel. Lisa seems to have a very limited vocabulary – as we said in class discussions, she speaks in choppy sentences. Not something you’d expect from a narrator. It’s one of the many things that makes us wary to trust her story, in addition to her telling us that she only thinks some things happened (Bender 27) and her frequent hallucinations. Narrators, especially of fairytales and fables, are supposed to be trustworthy, because their whole purpose is to convey the message. But as I said before, Lisa doesn’t seem interested in passing along any moral to us at all. Therefore, she feels no obligation to tell the story in a straightforward manner.

4:

Wording: Lisa tells us that she is not to blame for “it,” but we the readers

have absolutely no idea what it is.

She’s being very selective in the information she’s giving us. The main purpose

of this sentence for her is to tell us that she’s not at fault, not about what

she’s not at fault for. It’s hard to know whether she’s intentionally vague or

not, but it sure makes it a bumpy ride for us.

5:

Wording: This is pretty much a disclaimer. Lisa wants us to know straight away

that she had nothing to do with whatever harm befell her precious fire girl.

Telling us that it wasn’t her fault, in her mind, takes priority over

recounting the actual information. A fairytale narrator never does this. In

fact, when reading fairytales I seriously doubt that people ever suspect the

narrator of being guilty of anything. So again, Lisa wants to bend her position

as narrator a little. She still has the free will of a protagonist, yet she is

tasked with telling the story. Interesting that Bender combines two fairytale

“characters,” if you will, into one. But in addition, Lisa telling us that it

wasn’t her fault seems to suggest that she assumes we’d have cause to suspect

her. So she understands that she’s not a reliable narrator?

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)